| |

KJÖLUR OR KJALVEGUR.

I. GILHAGI — HVERAVELLIR.

The routes over Kjölur both from Húnavatns, —

Skagafjardar, and also from Eyjafjardar Sysla (Province), were used

not only in the Saga period, but also in later days, fairly

frequently in the summer. The members of the Legislative

Assembly used to pass this way to attend the meetings of

the "Althing", and the routes were also traversed by the

trading caravans in the time of the commercial monopoly, when

goods could alone be purchased in Reykjavík. Later, when

the Althing was dissolved (1800), and trading stations were

established on the coast around the whole Island, the

mountain routes lost much of their importance, and the people

gradually discontinued the use of them.

When moreover in the 18th century several accidents

happened on Kjalvegur this route was entirely given up.

Now it is only traversed at long intervals by visiting tourists

and harvesters passing from south to north, or by the

shepherds when they take the sheep up to the broad

summerpastures in the Spring and fetch them home again in the

fall.

In 1897 I passed over Kjölur from south to north and it

was at once clear to me that this ancient route could again

become of importance if it were marked out by cairns, so

that people could find the way even in foggy weather. Com-

munication between the northern and southern districts would

be greatly improved and it would be possible for an Ice-

lander to cross the uninhabited region in from 2 to 3 days.

This consideration together with a desire to open up a

Our companions: Ámundi, Indridi, owner of Gilhagi, Bödvar, Magnús

new route for tourists, brought me in 1898 again to cross

Kjölur. I was to mark all essential places where cairns should

be built to mark the route.

The artist Mr. Johs. Klein and myself had been carrying

out some investigations that year in the western and

northern districts of Iceland, and when these were completed

our little caravan of five persons and a score of horses, with

two tents, etc. etc. foregathered at Gilhagi farm on the eve-

ning of the 12'h of August.

We were accompanied by three attendants: Magnús

Vigfússon, a capital man who is now employed at the

Government House in Reykjavík, Bödvar Bjarnason, at that time

a theological student but who has since been ordained, and

Ámundi Ámundason. We were further accompanied half

way over Kjölur by two Icelanders from the Eyjafjördur

valley. One of these, Indridi was a peasant, 70 years of age,

from a neighbouring farm to Gilhagi. He was a sturdy old

man, who in spite of slight infirmity did not hesitate to

accompany us when I told him that his special knowledge

was indispensable to us for marking out the new bridle road

through the wastes, which he knew so well. His son-in-

law, the owner of Gilhagi, also came with us to accompany

the old man home again.

Gilhagi farm lay behind us. We had bidden its hospitable

dwellers farewell, and now we marched — the 13th August

Gilhagi.

— up the slopes above the farm with our little caravan, to

push on into Gilhagadalur. The way led steadily upward

towards the south west. After a good half hours ride we came

to some sheep pens belonging to the owner of Gilhagi. This

place is used every other year as a "Sel", a mountain

dairy for the cattle that are grazed on the mountains

pastures in the summer. In the winter a man must daily go the

long way up and back in all weathers to attend to the sheep,

which are turned out as much as possible. He has here a

warm shelter together with the wethers, where he can seek

refuge in bad weather. This year there was no ,"Sel"; but

two men and a couple of women, one of whom was married

and had her two children with her, were lying up at the

"Sel" houses to cut the hay. Inside the naked turf walls of

the stables they had made themselves as comfortable as

possible in their temporary home.

On we went up through Gilhagi dale until this opened

out on to the Plateau. Here we caught a glimpse of Hof-

sjokulls white cap before the clouds came driving down and

encircled it and all beyond it in their embrace. We now in-

clined more to the west and it was not long before we

reached the so called Litlisandur an undulating desolate sandy

and stony plain, where old Indridi nevertheless held the way

inspite of the fog. It cleared up at intervals and away in the

Indridi and ,"Tóki" crossing a river together.

south over the level Kjölur we saw the numerous

mountains in the horizon. It was a splendid sight. After passing

the sands we rode down a declivity and shortly after crossed

over Svarta. Indridi had brought his dog ,"Tóki", and it was

amusing to see them cross the rivers together. At a sign

from his master Tóki was on the horse's back in a flash,

and in this way they crossed all the rivers.

The "Sæluhús" at Adalmannsvötn

After in all 5 hours slow riding, we reached the pretty

lakes Adalmannsvötn. Here we made an halt at an old

dilapidated ,"Sæluhus" or hut for travellers and for shepherds

when collecting the sheep in the fall. It was blowing strongly

but Magnús made our coffee inside the Sæluhus, and we

took our meal in its lee, while all our horses, freed of their

burdens, grazed round about. The whistling swan breeds on

At Strangakvisl. — Hofsjökull in distance.

the lake in the summer, and we saw some of them in the

water. In clear weather Mcelifellshnjukur may be seen from

the lake.

Again we mounted and picked our way southwest in a

thick fog, over the deserted Thingmannahals, to the slopes

at Galtaru (6 hours ride from Gilhagi), where I had camped

in 1897, and where there was passable pasturage for the

horses. On that occasion we had a splendid view from here

over Kjölur, but now there lay fog everywhere. From here

we rode south along Blanda past Vékelshaugar hills, whose

most westerly knold lie close by the bridle paths. Here again

a Sæluhús and a little grass. It was evident that we were

on a route that had been much used in its time, for at

places there were as many as 20 old tracks side by side.

Until from ten to twenty years ago people from the nor-

thern parts came here to fetch Icelandic moss. At that time

at least one man from every farm was sent here with lea-

ding-horses to fetch the moss which was used as porridge,

and many tents sprang up here on the highland plain, but

now these excursions have ceased from lack of hands on

the farms.

In the fog we passed the lake Mannabeinavatn, and shortly

after crossed the many ramifications of the Strangakvisl to

pitch our camp on the southern side. (8 hours ride from

Gilhagi).

Crossing the Blanda.

We pitched the tents close by the foaming milk-white

water streaming by. The next day we started out again over

the still deserted plain. The weather was now good and the

glaciers and mountains had a fine appearance on the

horizon. Swarms of golden plover and curlew flew blithely over

the plain, and once now and again we encountered a few

sheep or colts. After a couple of hours ride we reached

Blanda, where old Indridi and his son-in-law were to

perform their master-piece and find a serviceable ford. With

rare assurance the old man steered his horse out into the

Old bridle paths at the Kjölur.

water, with his son-in-law following closely at his side. For

a while all went well, then suddenly both horses sank in;

but coolly and considerately they were led back again.

Several other places were then tried with no better success, but

finally they found a ford that was not too deep; but it led

direct to an aclivity, up which the horses had to be dragged.

Now the rest of us crossed with all the pack horses, the

water reaching as high as the horses' flanks.

Over Biskupsthúfa, where there is good pasturage, and

where we found a dead horse lying, — mournful remains of

a caravan that had recently passed, - Klein and I,

accompanied by Magnús, reached the little Rjúpnafell (Ptarmigan fell)

and climbed to its summit. Meanwhile Indridi led the caravan

to the hot springs of Hveravellir, where we were to camp.

On the way we had built small cairns at all difficult spots,

especially at the river crossings. These temporary signposts

were in the spring of 1899 replaced by larger and more

permanent stone cairns, which Magnus, with the help of two

others, built according to instructions.

We had now practically reached the divide between the

north and south watersheds. From the top of the hill,

Rjúpnafell, we had a capital view in a southerly direction over

the great lava field, Kjalhraun, which occupies a large

portion of the country between the northerly extremities of

Hofsjökull and Langjökull. The north wind whistled and froze

the marrow in our bones, but we crept for shelter behind a

huge block of rock which stands on the summit of the fell

like a gigantic Bautastone (stone monument). From here we

Kjalhraun with Strýtur, seen from Rjúpnafell.

watched our caravan disappear in the south west towards

Hveravellir, where the steam ascended from the hot springs

on the outskirts af Kjalhraun. This lava field lies like a very

flat dome with a small sharp eminence at the top, which

proved to be the edge of an extinct crater. From the crater

{Stn.tur} in prehistoric times the lava streamed out on all

sides into the hollow between the two great glaciers, up

towards the sources of Blanda in the north and right down

to Hvítá in the south.

On the eastern border of the lava field lies Dufufell,

often confused with Rjupnafell which lies more to the north;

in the distance are seen the summits of Kjalfell and Hruta-

fell with their glaciers; and in the extreme west the white

surface of Langjokull with its lower foothills. Looking be-

hind us we had a splendid view towards the north right away

to Mælifellshnjúk, and in the north east the heights north

of Hofsjökull, with the smaller conical hill Sáta (Haystack)

on the border of the latter.

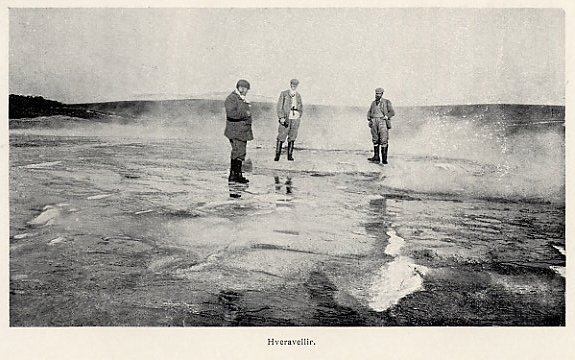

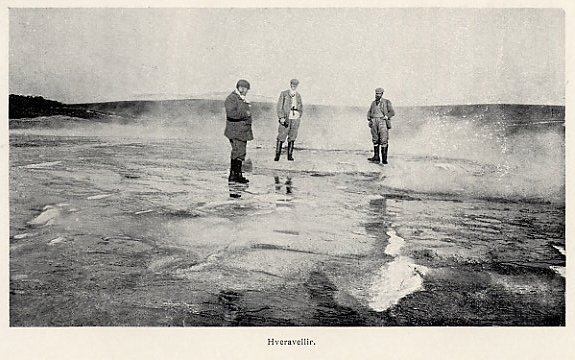

THE HOT SPRINGS AT HVERAVELLIR.

(Surveyed by Author in 1898).

---

When we had taken our photographs and sketches we led

the horses down the hill, and trotted over the flat

undulating sand plain toward the hot springs at Hveravellir. As we

approached these, we saw to our surprise four tents instead

of two, and so concluded there must be strangers there,

which also proved to be the case. They were the wellknown

English glacier-climber and Iceland guide, Mr H. F. Howell

(who was drowned a couple of years after in a river) and

two English tourists. They were of course just as surprised

as ourselves at the unexpected meeting.

Our tents were pitched on an ancient foursided site,

supposed to have been previously occupied by a Sosluhus, or

to have originated from a lawless, or perhaps from the

Landnams time, when a certain Torgeir spent a winter here.

Hveravellir was already in the time of the commonwealth a

wellknown baiting place. In the vicinity of the springs, there

is another similar spot, but this is only from the last

century, when one Eyvindur, a sheepstealer, stayed here for a time

to avoid capture. He cooked his food at the hot springs, and

contrived his dwelling in the fissure of a lava mound, while

he presumably "borrowed" his provisions from the public

pastures.

The hot springs are visible at a great distance from

Hveravellir, and the white steam shows up sharply against the black

background of lava. On nearer approach we see the milk

white silicious surfaces and the flame coloured sulphur

deposits in the outlet. The effect of these tones of colour is

one of wondrous beauty.

There are two domes of silicious sinter, separated by a

pond and a swampy hollow, the westerly being the least ac-

tive. On these domes are large and small springs, some of

which spout the water into the air, but only to the height

of a few feet. Several of them make a whistling spurting

sound, but most of them only bubble; nevertheless their

splendid colours are exceedingly attractive. The activity of

the springs is steadily on the wane. Eggert Olafsson, who

visited them in 1752, speaks of "Öskurhóll" as a bellowing

eminence which ejected steam with a sound of thunder,

whereas this has now entirely ceased. Also since Henderson

visited the springs in 1815 their strength is appreciably less.

Thoroddsen surveyed them in 1888, and his description of

them, accompanied by a plan, appeared in the Swedish pe-

riodical ,"Ymer" for 1889. In the lava south of the springs,

may be seen further distinct traces of old springs, while in

many places, steam still rises from cracks and fissures.

The next morning Mr Howell rode off to the north east to

Eyjafjördur via Vatnahjallavegur, arriving at his destination

two days later. |

|

![]() Zurück zu Inhalt

Zurück zu Inhalt![]() nächstes Kapitel

nächstes Kapitel