|

An exceptionally interesting branch excursion may be made

from Gránanes to the Sulphur Springs at Kerlingarfjöll, which

I will describe from my experiences in 1897. Gránanes is a

low grassy promontory in the fork of the two tributary rivers

which form Svartu. We arrived there on the 8th August. It

was twilight on the plains by the time the tents were

pitched and Ihe camp fire lighted, but from a little eminence,

we could see that is was still light on the hilltops. On the

dark plain the pools and the river were depicted in shining

whiteness. The tents and

horses could be faintly

descried, and the red glare

of the camp-fire shone

like a star in a dark

firmament.

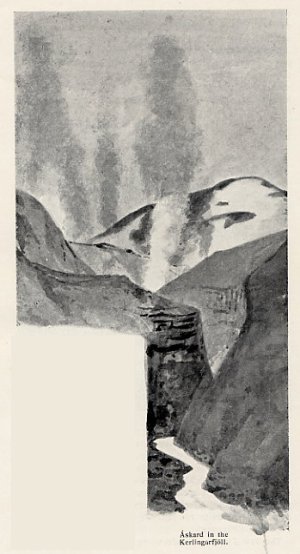

Áskard in the Kerlingarfjöll

whiteness. The tents and

horses could be faintly

descried, and the red glare

of the camp-fire shone

like a star in a dark

firmament.

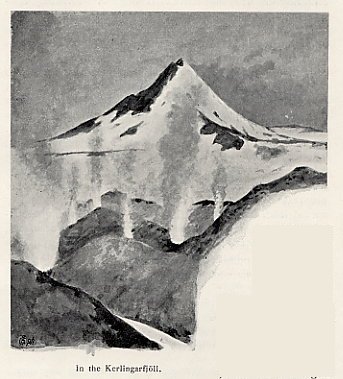

Over the dark fantastic

hill flanks the snow clad

summits of Kerlingarfjöll

(over 3600 feet), on which

the clear evening tints

still rested, could be seen

away to the south east.

A solitary wild duck

started up near the

foaming foss and disappeared

in the gloom along the

river, a single cry from a golden plover or curlew, and all

was still, the only sound that reached us being from the

horses munching their fodder.

The 9th August 1897 we struck camp and set out for

Kerlingarfjöll. The country passed through here is an

undulating highland plain, bare of vegetation and intersected by a

mumber of streams and rivers, which flow partly from

Hofsjökull and partly from the Kerlingarfjöll mountains,

eventually joining to form Jokulkvisl.

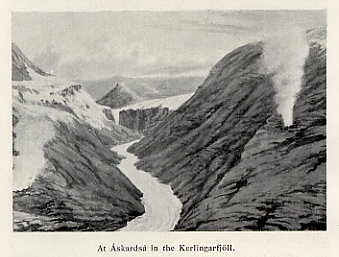

From some heights north of Kerlingarfjöll we got a

magnificient view of the mountain chain. About halfway between

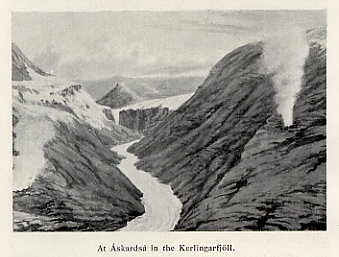

At Áskardsá in the Kerlingarfjöll.

its eastern and western extremities is a valley, from which

a deep-cut riverbed (Áskardsá) wends its way out to

Jökulkvísl, which lay between us and the mountains.

A faint mist up in the valley indicated the position of the

hot springs. The country around was everywhere naked and

bare and almost without vegetation.

We passed over Jökulkvísl, where the water level was not

very high. In the deepest spots however, it reached the hor-

ses flanks. In a little dale which we reached by passing over

a ridge, we found a modest pasture with poorish grass, and

pitched our camp here in the vicinity of a Sæluhús, used

by the shepherds in the fall. We had been 3 hours on the

way from Gránanes.

The 11th August we rode up to the valley with the boiling

springs in about an hour, the latter part of the journey being

performed over steep snow-clad slopes. Leaving the horses

at the mouth of the valley we proceeded on foot. Standing

on the brink of the valley, we saw towards the east, Áskardsa,

winding its way through the grand giddy cleft down toward

the camp. On the east slope of the valley, which was steep

and unapproachable, we saw steam springing from a large

chasm and rising into the air in a mighty column, while the

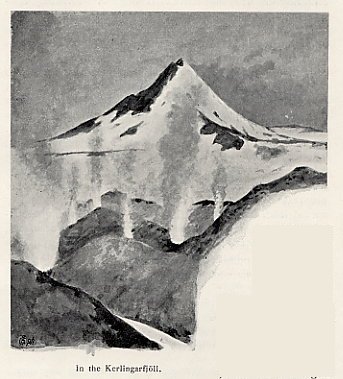

In the Kerlingarfjöll.

hissing sound from the fissure resembled the escape of a steam

funnel. Beyond from the cleft to the north, we looked out over the

broad level highland plain with Hofsjökull on the right.

Far far away on the horizon could be discerned a small

conical summit — Mælifellshnjúkur — 70 miles away. Up the

valley the perpetual snow lay on the peaks and stretched its

long arms down into the dales. The country below the snow

fields appeared as a baked up earth or clay mass, absolutely

bare of vegetation, and pierced and furrowed by deep dales

and clefts, which, as Thoroddsen remarks ,"fork like the

branches of a great tree from one trunk". On all sides, large and

smaller columns of steam rose into the air.

The colours of this earth formation were light, but of great

variety, slopes and crevices shining often with the most gla-

ring colour, daubs of white, yellow, red, pink, blue and green

being muddled together with the most outrageous discord, so

as to form quite an eyesore. We wandered each for himself

in these marvellous surroundings, which would have formed

an excellent setting for the lower regions. I descended to

the bed of the stream; removed my boots and waded forward,

following the deep and narrow windings with soft steep

claybanks on either side. The water was a yellowish white colour

and opaque, so that I could only proceed with the greatest

circumspection. As melted ice and snow were mixed with the

hot water from the springs, it was quite cold. One moment I

passed steaming springs, the next small seething reservoirs

also steaming, or I heard a crackling sound like as though small

water columns were spouted into the air. Here and there

dark fissures emitted rumbling or hissing sounds from the

bowels of the earth, accompanied by rising mists of steam.

At short intervals small valleys branched to right and left,

and I saw springs steaming in all and heard their seething

and bubbling. As I advanced, the banks became less steep

and I ventured myself upon them. After a couple of hours

progress I reached the innermost springs. Here the valley

spread itself out and assimilated with the surrounding moun-

tain slopes. It was interesting to see where, in some places,

the small glaciers spread themselves round the springs; here

it appeared as though the steam arose direct out of the snow.

Occasionally the snow reached right down to the river, and

formed bridges of ice and snow over it, under which I

passed. Large quantities of sulphur, obsidian and pumicestone

abounded everywhere.

After climbing a mountain top and obtaining a view of

the territory to the south, I returned to the camp the same

way I had come.

The grass here was now nearly all eaten up, and there

was no more firewood in the neighbourhood, so it was high

time to take our departure, but before leaving, we scaled a

mountain summit to get a view over Kjölur.

Wherever we turned there was a surprising variation and

richness in the scenes spread out before us. Their beauty

was quite uncommon, and our eyes could scarcely conceive

at once all that we saw. To right and to left, before and

behind us, were pictures innumerable, each with its own

attraction.

Due north we looked out over the low plain stretching

away mile upon mile, dark brown and monotonous it lay

before us. Swamps and rivers, small lakes and streams

glistened in the proximity of the glaciers. Peaceful and quiet,

attractive and pleasant — apparently with hindrance — it

stretched itself as far as the eye could reach away to the

coast-hills of the north. Here the picture changed again. It

was as if quite other regions beckoned to us from away out

there in the infinite distance. The mountains lay like a dark

jagged streak at the extremity of the plain, and central in

this chain Mcelifellshnjukur raises its conical summit high above

the rest, dividing the horizon into two symmetrical parts of

equal dimensions on either side.

The warm blood-red tints of the glowing evening sun

lightened up the heavens over this distant horizon, and seemed

to tell of inhabited regions and snug homes there.

To the west on the plain lay here and there isolated

pyramidal flat-topped hills in soft velvety tones (Kjalfell,

Dúfufell, Rjúpnafell), forming the most advanced outposts among

Langsjökulls protecting foothills and extending arms.

A canopy of clouds hid the uppermost plains of

Langjökull. Over the glacier's perpetual ice hung large whitish —

often silver-coloured — irregular and enigmatical fog clouds.

Twilight brooded in the vales between the steep lofty

heights of the foothills.

The clouds had gathered on the flat glacier summit of the

splendid foothill Hrutafell like a light thin pillow, the

reflection from which fell glimmering over the mountain side

on snow-clad clefts and crevices.

A grand, noble, mighty picture.

On the right of the plain lay Hofsjokall's great ice-field.

Here the arc of the great glacier showed up distinctly and

sharply against the clear transparent heavens, which had a

greyish tint.

Behind us lay the warm light yellow Lipari summits of

Kerlingarfjöll partly covered by snow. Some solitary sheep

ventured on the snowy slopes for the refreshing coolness.

The narrow valley with its dizzy depths wound down from

the mountains in a dark serpentine streak. The farthest

summit towards the east (Lodmundur) was formed of a grand

almost coal-black peak with white shining strips of snow.

Never from one spot have I seen such an abundance of

beauteous scenery. All was silent and still except the

rumbling and seething in the valley of the hot springs. A raven's

hoarse croak broke the peaceful stillness. We mounted our

horses and rode back to Gránanes.

|

![]() Zurück zu Inhalt

Zurück zu Inhalt![]() nächstes Kapitel

nächstes Kapitel