| |

SKAGAFJORDS DALE

is divided by Hjeradsvotn, a large swollen river, drawing

its waters from the melted ice from Hofsjokull, and from

'hill and dale. The valley is noted for its fine meadows; its

magnificent frame of hills, — especially on the east side,

where numberless small dales break into the hills —; and

in fact for its pretty scenery in general. Three or four rows

of farms lie in the meadows on the slopes, principally on

the west side. An exceptional breed of horses is raised in

this verdant valley and the traveller who is fortunate enough

to procure his mount from here will not regret it.

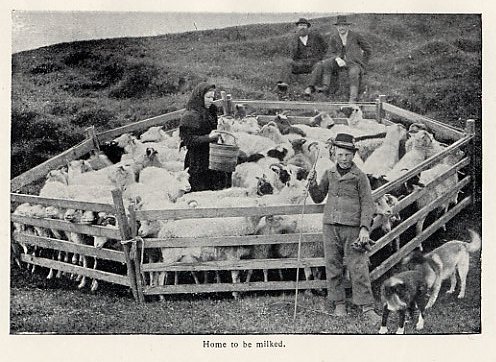

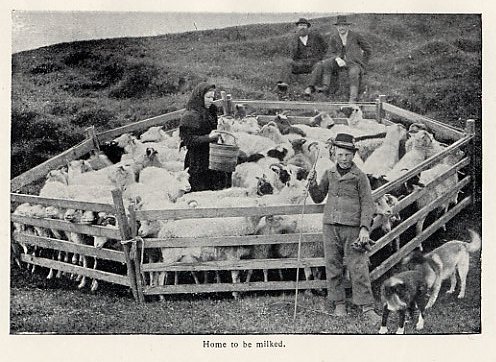

Home to be milked

The summer is short in Iceland, far too short, and no

time must be lost if all the necessary work is to be got

through betimes. First and foremost the hay must be saved,

for fodder for the cows, horses and sheep for the winter is

an essential for these, and consequently for the Icelanders

themselves. Agriculture is scarcely known in Iceland. The

traveller who traverses the valleys of Iceland in the summer

sees therefore haymakers, men and women together, hard

at work in the home fields of the farms or in the meadows;

he hears every where the sharpening of the scythes and

sees their rythmic swing, or he meets the ponies loaded with

large bundles of hay and being led in single file by a youth

or girl, who is often mounted on the leader. May be the girl

is sitting astride a mans saddle, red-cheeked and bonny and

unconscious of impropriety. When the little caravan reaches

home to the farm the hay is stacked in long ricks in the

hay-yard or is put in sheds.

Away up the hillsides are the milch sheep, generally ten-

ded by an old man or a boy (smali). Towards evening the

flock is driven home to the farm to be milked and the sing

song cry of the shepherd, as he sends his dog up after them,

may be heard.

The cows are run in the meadows or on the hills, and the

horses likewise; but far far away on the other side of the

fell many miles from the farms — and away up on the

highland plain which stretches towards the Glaciers, sheep and

colts run wild the whole summer through.

On a Sunday all work ceases — unless the hay harvest

makes it absolutely necessary to work — and the scythes

and rakes find a resting place on the roofs of the houses.

The people dress themselves, catch and saddle up the

horses — and off they go at a rare pace to church. The women

take the smallest children with them on the saddle, those

a little older are secured on their own horses, and the big-

ger ones ride of themselves, the boys with their feet stuck

in the stirrup straps in lieu of stirrups. The dogs bring up

the rear. And so from all the farms a procession moves

churchward over stick and stone and brook and beck. They

meet early at the church, for there is much to talk over:

The old ask the news, the young — they soon find one

another and many a promise which bound for life and death,

is given here in the churchyard among the grass-grown

graves and crumbling crosses.

But the women, before entering the church pay a visit to

the farm hard by, to lay aside their cloaks and hats or

riding bonnets, and fasten the little tasselled caps on their

heads; or perhaps, if it is a special festival, even to deck

themselves out in the proper festal garb. This custom is

however on the wane in the villages.

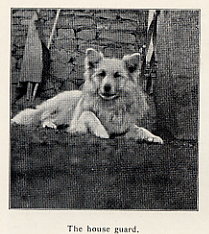

The house guard.

old Icelandic churches built of turfs, they may

be found in the church itself under the roof. The last of

these old churches are to be found in Skagafjords dale.

A choir is often formed of young women who lead the

singing. They are all attractive, and neatly clad in becoming

dresses.

The day before one may have seen them in their work-a-

day attire raking hay in the home-fields, with dishevelled

locks partly confined by a handkerchief at the back of the

head, and with short skirts and thick brown woolen stockings

fastened at the knee with leather garters. Firmly and boldly

they marched about their work, smartly and ably they sprang

over the ditches and puddles in their skin shoes.

Now the clergyman enters the pulpit; he reads his sermon,

the usual practice in Iceland. After the service there may

be Holy Communion or a Christening: though seldom the

latter, for the children are generally christened at home. If

the Parsonage is near the church it may happen that coffee

is provided for the congregation in the "Badstofa". This

room is without ceiling. The windows are in the roof, and

there is a row of bedsteads along each side; there is seldom

a stove, but it is easily kept warm in the winter when all

the farm hands are there, and all the lamps lighted. This

room is both living room and sleeping room for all

engaged on the farm, married and single, youths and maidens.

Such an arrangement could scarcely be dreamt of in

Reykjavík or at the trading stations, but in the country this old

custom is still adhered to, and yet morals are in no way

worse here than where such indiscriminate mixing of the

sexes is unheard of. Force of habit is so strong that young

girls without shame undress and go to bed in the same

sleeping room as the men.

Sometimes the end of the "Badstofa" is partitioned off,

and the master of the house and his wife sleep here. The travel-

ler however is generally accomodated in the "Stofa", a small

dwelling house apart; but attendants and guides usually sleep

in the common room.

Finally one little party after another mount their horses.

The swains especially start off at a furious pace, while the

girls hop boldly into the saddle and follow them.

A Sunday calm rests over the valley. There is no sound

of sharpening scythes, no caravan with hay, no load

homeward bound from the trading station. Only the merry

mounted party wending home from church. Almost imperceptibly

the wind stirs the grass on the roof of the old church —

on the graves beside it, and on the roof of the farm house

where the watch dog lies on guard. Up in the hills a fog

encircles the highest peak; but down in the broad

meadows by the rivers winding course, and on the dark clumps

of houses, whence the blue smoke rises aloft, the sun shines,

— and out on the horizon the blue sea is roaring.

Sunday evening comes. Here and there a neighbourly call

is being paid at an adjacent farm. In the late twilight hours,

when the hay is smelling sweetly in the home fields the

callers finally mount their horses and turn their heads home-

ward.

The Skagafjord Valley is 6 to 8 miles wide and 20 to 25

miles long. At the upper end it divides into the Eystri- and

Vestridalur, long deep and narrow valleys uninhabited at

their upper ends nearest Hofsjokull. From these valleys come

the east and west glacier streams, the principle tributaries

to Hjeradsvotn. Gradually the river reaches out of the

hills into the more open country, and finally at its mouth

it is split in two by the large Island Hegranes. Throughout

its whole course however it is rapid and deep, and can only

be forded at a couple of places and not even there at all ti-

mes. Ferries, overhead ferries, fords, and bridges are used

in communication between the two valley-sides. These are

to be found at the following places:

| |

Fording place in Eystridalur opposite Aboer, and at one

point farther up in the uninhabited part.

Bridge in Vestridalur at Goddalir.

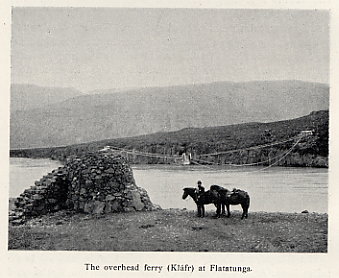

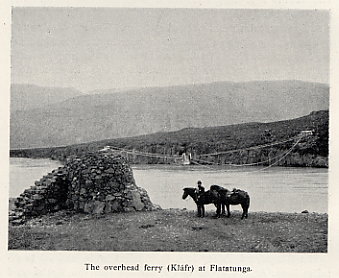

Overhead Ferry (Kláfr) at Flatatunga.

Ford opposite Silfrastadir.

Ford opposite Miklibær.

Ferry-boat "Akraferja" between Flugumýri and Vidimýri.

Bridge over the east arm of Hjeradsvotn below Hofstadir

and finally.

Ferry-boat over the west arm of Hjeradsvotn, west of He-

granes, an old Thing place.

|

At the ferries the loose horses often swim over, while the

people and pack-horses go on the ferry-boat. The ferrymans

The overhead ferry (Kláfr) at Flatatunga.

helper is on the spot active and smart at helping. The

horses which are not packed are driven out into the water with

stones. They keep together in a bunch with their heads

upstream, so that the weaker horses swim in the lee of the

stronger; snorting and groaning, with wide-stretched nostrils

they swim gamely over. The moment they reach shore they

shake the water from them and roll in the sand, then off to

the nearest pasture.

FROM SAUDARKROKR TO GILHAGI

there is a choice of the two following routes:

1) Along the west side of the valley, passing

Hafsteinsstadir, — Reynistadir, — Glaumbær, — Vidimyri (church

built with Turfs), — and Moelifell; one day

2) Along the east side of the valley including a side trip to

Holar, the old episcopal residence; two days.

1st Day: Saudarkrokr — Hegranes Hofstadir Holar (church)

and back to Hofstadir (Turf church), where is

to be spent the night.

2nd Day: Hofstadir— Flugumýri (Turf church) — Miklibær

— Silfrastadir — over Nordurá ford —

Flatatunga — by overhead ferry over Hjeradsvötn

and from there to Gilhagi. From the ferry one

must first ride about 1 1/2 hours in a southerly

direction, before it is possible to turn W NW

towards Gilhagi, because the country is very

swampy on the road direct towards Gilhagi from

the ferry.

3) Finally a combination of these two routes may be made,

making use of ferries, bridges and ford. This will take

two days.

Excursions in Eystri- and Vestridalur from Gilhagi take at

least two days. Here are a number of deserted dwellings

dating from the middle-ages, proving that the settlements

at that period stretched much deeper into the country than

at the present day.

|

|

![]() Zurück zu Inhalt

Zurück zu Inhalt![]() nächstes Kapitel

nächstes Kapitel